Vulnerabilities in Ruby on Rails Application

Published: Jul 17th, 2021Note: [This is incomplete post it will be edited]

Injection Flaws

Generally injection vulnerabilities occur when untrusted data is placed into data that is passed to some sort of compiler or interpreter on the back-end server, where the data might, if it’s formatted in a particular way, be treated as something other than data.

Command Injection

OS Command Injection CWE-78: OS Command Injection is a type of injection vulnerability wherein commands injected by an attacker are executed as system commands on the host operating system.

Not to be confused with Code Injection Code Injection is the general term for attack types which consist of injecting code that is then interpreted/executed by the application. , OS Command Injection extends the preset functionality of the application to execute system commands, whereas Code Injection attacks allow the attacker to add their own code to be executed by the application. In certain circumstances, Code Injection could be promoted to OS Command Injection by using the facilities provided by the language.

The vulnerable example for this problem has always been API calls that directly call the system command interpreter without any validation.

Vulnerable example

The following snippet contains a Ruby on Rails model that executes the nslookup command to resolve the host supplied by the user.

class Resolver < ActiveRecord::Base

def self.lookup(hostname)

system("nslookup #{hostname}")

end

endSince the hostname is simply interpolated into the string command and executed on a subshell, an attacker could stack another command using ; in the GET parameter to inject additional commands:

> nslookup x;cat /etc/passwd

Server: 8.8.8.8

Address: 8.8.8.8#53

** server can't find x: NXDOMAIN

root:x:0:0::/root:/bin/bash

bin:x:1:1::/:/usr/bin/nologin

daemon:x:2:2::/:/usr/bin/nologinRemediation

Ruby has a native API to execute commands. Many of the APIs ingest arguments as a list, which shall be always preferred over sending multiple arguments as single strings. This helps to avoid introducing command injection vulnerabilities.

exec([cmdname, argv0], arg1, ...) # Or exec(cmdname, arg1, ...)

system([cmdname, argv0], arg1, ...) # Or system(cmdname, arg1, ...)

IO.popen([env, [cmdname, argv0], arg1, ..., opts]) # Or IO.popen([env, cmdname, argv1, arg1, ..., opts])

Open3.popen3([cmdname, argv0], arg1, ...) {} # Methods popen2 and popen2e also exist

Open3.capture2([cmdname, argv0], arg1, ...) {} # Methods capture2 and capture2e also exitsPassing the command as a single string introduces the vulnerability:

system("nslookup #{hostname}") # WRONGSecure example

Passing the command as a list of arguments is the safer approach that should always be used, but it might be vulnerable to argument injection depending on the binary.

system("nslookup", hostname)Some methods only accept the command argument as a single string and are prone to introducing an injection vulnerability. These functions should not be used, or at least used very carefully, to escape or filter out the characters against an allow list (e.g. filtering out everything that is not alphanumeric).

`cmd` # Or Kernel.`("cmd")

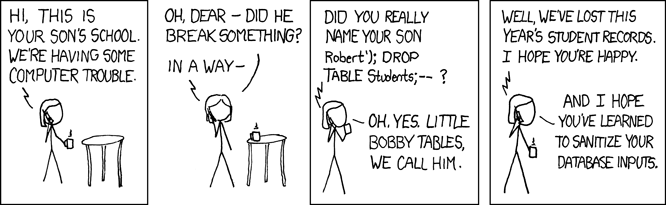

%x( cmd )SQL Injection

SQL injection SQL Injection is a common attack that uses malicious SQL code for backend database manipulation to access information that was not intended to be displayed or changed.

An attacker can use SQL Injection to manipulate an SQL query via the input data from the client to the application, thus forcing the SQL server to execute an unintended operation constructed using untrusted input.

Applications are vulnerable to attacks when user-supplied data is not validated, filtered for escape characters or sanitized by the application.

Remediation

To avoid SQL injection vulnerabilities, developers need to use parameterized queries Query Parameterization for Ruby on Rails. , specifying placeholders for parameters so that they are not considered as a part of the SQL command; rather, as solely data by the database.

When working with legacy systems, developers need to escape inputs before adding them to the query. Object relational mappers (ORMs) make this easier for the developer; however, they are not a panacea, with the underlying mitigations still entirely relevant: untrusted data needs to be validated, query concatenation should be avoided unless absolutely necessary, and minimizing unnecessary SQL account privileges is crucial.

Ruby on Rails provides an interface called Active Record Active Record Basics. , an object-relational mapping (ORM) abstraction that facilitates database access. The following snippet of code displays the User model performing email and password validation, as well as conducting some authenticated actions:

Vulnerable example

if User.where("email = '#{address}' and password = '#{password}'").exists?

# Do something as authenticated in user

endSince the SQL query is built by concatenating address and password user inputs, an attacker could manipulate the query to bypass the authentication check.

For example, by injecting mail@attacker.com') or ('1'='1 and an incorrect password in the address field, the query becomes:

SELECT `users`.* FROM `users` WHERE (email = 'mail@attacker.com') or ('1'='1' and password = 'wrongpassword')The manipulated query returns the user record whose email equals mail@attacker.com or if 1 equals 1 and whose password equals wrongpassword. Since the password is not relevant anymore but the WHERE clause is true, an attacker could log in without having a valid password simply with a valid e-mail.

Active Record has a built-in filter for special SQL characters, which will escape ', ", NULL character and line breaks. Using Model.find(id) or Model.find_by_some thing(something) automatically applies this countermeasure. But in SQL fragments, especially in conditions fragments where(), the connection.execute() or Model.find_by_sql() methods, it has to be applied manually.

Secure example

Instead of concatenating the user-provided variables to the condition string, you can pass an array to sanitize tainted strings like this:

User.where("email = ? AND password = ?", address, password).exists?You can also pass a hash for the same result:

User.where(email: address, password: password).exists?The array or hash form is only available in model instances. You can try sanitize_sql() ActiveRecord::Sanitization methods elsewhere.

Authentication Flaws

There is an old saying that used often in application security:

“don’t reinvent the wheel”

That is exactly the same case for this topic.

Broken Authorization

Broken Authorization OWASP Broken Authorization (also known as Broken Access Control or Privilege Escalation) is the hypernym for a range of flaws that arise due to the ineffective implementation of authorization checks used to designate user access privileges.

Different users are permitted or denied access to various content and functions in adequately designed and implemented authorization frameworks depending on the user’s designated role and corresponding privileges.

For example, in a web application, authorization is subject to authentication and session management. However, designing authorization across dynamic systems is complex, and may result in inconsistent mechanisms being written as the applications evolve: authentication libraries and protocols change, user roles do as well, more users come, users go, some users are (not) removed when gone… access control design decisions are made not by technology, but by humans, so the potential for error is high and ever-present.

In a successful attack, a malicious actor may be able to access unauthorized content, change or delete content, perform functions, and even assume full control of site administration. Once this level of compromise has been achieved, the damage of the attack is limited only by the privileges granted to the impersonated victim.

Attack Scenarios

From the perspective of the user, there are two main categories of authorization controls to consider:

- Horizontal Authorization Controls

- Vertical Authorization Controls

Horizontal Authorization Control Bypass

Bypassing Horizontal Authorization Controls describes the act of an unprivileged user gaining access to other users’ accounts that possess equal privileges.

For example, imagine an application accepting unverified data in a method call downstream to retrieve account information. An attacker could easily modify the accountId parameter in the HTTP Request to retrieve data from one or even multiple other users’ accounts.

The application uses unverified data in a method call downstream to retrieve account information:

http://example.com/account?accountId=7800001

http://example.com/account?accountId=7800002

Insecure Direct Object References Insecure Direct Object References , or IDOR, is a related scenario involving user-supplied input being utilized to access objects directly.

Vertical Authorization Control Bypass

Vertical Authorization Control bypasses describe the upwards use of access. That is, when a user with a certain level of privilege can indicate that they possess some higher level of access, like administrative level access, to the application.

In this example, an attacker has browsed to an administrative URL, where admin rights should be required to access the adin page.

http://example.com/user/account

http://example.com/admin/panel

If the application does not check whether the role of the session user matches the role required to access the resource, a user without admin privileges will be able to access the page by simply knowing/guessing the target URL and browsing to it.

Vulnerable example

The following Ruby snippet shows a Ruby on Rails controller that pulls the user from the request parameter, looking up the user email passed as a parameter in the URL:

def restricted

@user = User.find_by(email: params[:email])

if !(@user)

flash[:error] = "Sorry, invalid user"

redirect_to public_index_path

end

endThis could be abused by any user to access the restricted API by invoking it, passing the email address of another legitimate user as a parameter.

Remediation

User management and authentication are not native features of Rails, but they can easily be added by either writing the code or adding a gem, such as Devise.

Authorized user

A simple manual approach is to add a method that retrieves the current, logged-in user looking up active sessions to the Application Controller. It is frequent to add e.g. current_user method in the ApplicationController class to make sure every controller in the application inherits it.

class ApplicationController < ActionController::Base

def current_user

User.find_by(id: session[:user_id])

end

endSuch method takes the user ID value from the user’s session and is resilient against tampering. It can be easily invoked by other controllers such as the one shown in this snippet:

def restricted

@user = current_user

if !(@user)

flash[:error] = "Sorry, invalid user"

redirect_to public_index_path

end

endRole-based authorization

It’s common to set access restrictions based on roles in order to check if a user has a specific role (such as administrator) and either allow access or redirect with an “Access Denied” message. Roles are attributes associated with a user account and implemented in a User schema and model.

The simplest scenario is a binary role scenario when a user can be either an administrator or an ordinary user. Add a boolean attribute to the User schema to indicate whether a user is an administrator or not and check the role checking the @user.admin attribute value:

def restricted

@user = current_user

if !(@user) || !(@user.admin)

flash[:error] = "Sorry, the user is not an administrator"

redirect_to public_index_path

end

endController filters

Role-base controls can be also enforced using “before” filters in the Controller classes in order to halt the request cycle if a condition is not met. In the following snippet, the restricted method can be invoked only by users who satisfy the administrative filter:

class AdminController < ApplicationController

before_filter :administrative

def restricted

@user = current_user

if !(@user) || !(@user.admin)

flash[:error] = "Sorry, the user is not an administrator"

redirect_to public_index_path

end

end

private

def administrative

if !current_user.admin

redirect_to public_index_path

end

end

endFilters are inherited, so if you set a filter on ApplicationController, it will be run on every controller in your application.

Client-side Validation Flaws

Cross-Site Scripting

Cross-Site Scripting (otherwise known as XSS) is a vulnerability that allows a malicious actor to manipulate a legitimate user’s interactions with a vulnerable web application. Attackers exploit this to bypass the same origin policy Same-origin policy , often allowing them to perform any actions that the target user would normally perform, including gaining access to their data. In cases where the victim user has privileged application access, the attacker may use XSS to gain control of the application.

XSS attacks can result in the disclosure of the user’s session cookie, allowing an attacker to hijack the user’s session and take over the account. Even though HTTPOnly is used to protect cookies, an attacker can still execute actions on behalf of the user in the context of the affected website.

XSS attacks can generally be divided into the following three categories:

Reflected XSS

Reflected XSS attacks arise when a web server reflects injected script, such as a search result, an error message, or any other response that includes some or all of the input sent to the server as part of the request.

The attack is then delivered to the victim through another route (e.g. e-mail or alternative website), thus tricking the user into clicking on a malicious link. The injected code travels to the vulnerable website, which reflects the attack payload back to the user’s browser. The browser then executes the code because it came from a “trusted” server

Stored XSS

In the Stored XSS attack, the injected script is stored on the target application as legitimate content, such as a message in a forum, a comment in a blog post, etc. The injected code is stored in the database and sent to the users when it is retrieved by accessing the injected content, executing the attack payload in the victim’s browser.

Dom-based XSS

DOM-based XSS vulnerabilities usually occur when the JavaScript in a page takes user-provided data from a source in the HTML, such as the document.location, and passes it to a JavaScript function that allows JavaScript code to be run, such as innerHTML(). The classic attack delivers the payload to the victim through another route (e.g. e-mail or alternative website) and thus tricks the user into visiting a malicious link. The exploitation is client-side, and the code is immediately executed in the user’s browser.

Remediation

XSS attacks can be mitigated by performing appropriate server-side validation and escaping. Remediation relies on performing Output Encoding (e.g. using an escape syntax) for the type of HTML context where untrusted data is reflected into.

Input Validation Input Validation

- Exact Match: Only accept values from a finite list of known values.

- Allow list: If a list of all the possible values can’t be created, accept only known good data and reject all unexpected input.

- Deny list: If an allow-list approach is not feasible (on free form text areas, for example) reject all known bad values.

Output Encoding

Output Encoding Output encoding is used to convert untrusted input into a safe form where the input is displayed as data to the user without executing as code in the browser. Output Encoding is performed when the data leaves the application to a downstream component. The table below lists the possible downstream contexts where the untrusted input could be used:

Defense in Depth

Content Security Policy (CSP)

The Content Security Policy (CSP) Content Security Policy is a browser mechanism that enables the creation of source allow lists for client-side resources of web applications e.g. JavaScript, CSS, images etc. CSP via a special HTTP header instructs the browser to only execute or render resources from those sources.

For example:

Content-Security-Policy: default-src: 'self'; script-src: 'self' static.domain.tld

The above CSP will instruct the web browser to load all resources only from the page’s origin, and JavaScript source code files additionally from static.domain.tld. For more details on Content Security Policy, including what it does and how to use it, see this article.

X-XSS-Protection Header

This HTTP response header enables the Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) filter built into some modern web browsers. The header is usually enabled by default anyway, so its role is to re-enable the filter for a particular website if it was disabled by the user.

Rails by Default

Rails provides ERB (Embedded RuBy) as a template engine to generate dynamic web pages.

Before Rails 3.x, the function escapeHTML() (or its alias h()) needed to be called to escape HTML output in all templates, but in more recent versions, it is on by default in all of the view templates.

To bypass the automatic encoding in recent Rails versions, calling html_safe or prepending raw on a string sets the string as HTML Safe, and ERB inserts it unaltered into the output.

Strings in JavaScript contexts should be explicitly encoded by prepending escape_javascript or j to the variable. This escaping does not encode generic JavaScript code and should only be used with JavaScript string literals.

| Context | Code | Rails >=3.x ERB Encoding mechanisms |

|---|---|---|

| HTML Code and Attribute | <%= user-controlled-variable %> |

HTML Escaped Encode data for use in HTML using HTML entity encoding |

| JavaScript Strings Literals | <script>var id = '<%= escape_javascript user-controlled-variable %>';</script> |

Escapes carriage returns and single and double quotes for JavaScript strings. Encode data for insertion inside a JavaScript string |

Handling User Input

-

Always validate user input that may eventually be displayed to other users. Attempting to blacklist characters, strings or sanitize input tends to be ineffective (see examples of how to bypass such blacklists). A whitelisting approach is usually safer. Mitigates multiple XSS attacks.

-

When using regex for input validation, use \A and \z to match string beginning and end. Do not use ^ and $ as anchors. Mitigates XSS attacks that involve slipping JS code after line breaks, such as

me@example.com\n<script>dangerous_stuff();</script>. -

Do not trust validations implemented at the client (frontend) as most implementations can be bypassed. Always (re)validate at the server.

Output Escaping & Sanitization

-

Escape all HTML output. Rails does that by default, but calling html_safe or raw at the view suppresses escaping. Look for calls to these methods in the entire project, check if you are generating HTML from user-inputted strings and if those strings are effectively validated. Note that there are dozens of ways to evade validation. If possible, avoid calling html_safe and raw altogether.

-

Always enclose attribute values with double quotes. Even without html_safe, it is possible to introduce cross-site scripting into templates with unquoted attributes. In the following code <p class=<%= params[:style] %>…</p>, an attacker can insert a space into the style parameter and suddenly the payload is outside the attribute value and they can insert their own payload. And when a victim mouses over the paragraph, the XSS payload will fire.

-

Rendering JSON inside of HTML templates is tricky. You can’t just HTML escape JSON, especially when inserting it into a script context, because double-quotes will be escaped and break the code. But it isn’t safe to not escape it, because browsers will treat a </script> tag as HTML no matter where it is. The Rails documentation recommends always using json_escape just in case to_json is overridden or the value is not valid JSON. Mitigates XSS attacks.

-

Be careful when using render inline: …. The value passed in will be treated like an ERB template by default. Take a look at this code: render inline: “Thanks #{@user.name}!”. Assuming users can set their own name, an attacker might set their name to <%= rm -rf / %> which will execute rm -rf / on the server! This is called Server Side Template Injection and it allows arbitrary code execution (RCE) on the server. If you must use an inline template treat all input the same as you would in a regular ERB template: render inline: “Thanks <%= @user.name %>”. Mitigates XSS attacks.

-

Avoid sending user inputted strings in e-mails to other users. Attackers may enter a malicious URL in a free text field that is not intended to contain URLs and does not provide URL validation. Most e-mail clients display URLs as links. Mitigates XSS, phishing, malware infection and other attacks.

-

If an I18n key ends up with _html, it will automatically be marked as html safe while the key interpolations will be escaped! See (example code).